THEA Bridge

THEA Decentralized Bridge - White Paper

Protocol: THEA stands for Threshold ECDSA, or Threshold Signature scheme applied through Elliptic Curve Cryptography

Abstract: Polkadex wants to make use of an efficient and inexpensive decentralized bridge to layer 1 blockchains to allow its assets to interoperate with the Substrate-based Polkadex blockchain. This will allow assets from other blockchains to be easily ported and traded on the Polkadex orderbook exchange, without affecting the user experience. The purpose of this whitepaper is to present an alternative to existing bridges that use expensive on-chain multisig based smart contracts or centralized relayer sets to bridge assets from Layer 1 to Layer 2.

Co-authored

Vivek Prasannan |  Gautham J |

Table of contents

- What is a Bridge?

- Types of bridges available

- Bridge solution

- Combining TSS with blockchains

- TSS vs Multisig

- TSS vs smart contracts

- THEA implementation

- Lightclients

- THEA

- References

What is a Bridge?

A bridge is responsible for holding the assets on a layer-1 blockchain while the same assets are released on another ( external) service. It defines who has custody of the funds and the conditions that must be satisfied before the assets can be unlocked.

Porting assets from one blockchain to another blockchain comes with a myriad of benefits. First, the blockchain onto which you port assets might be cheaper and faster than its native blockchain. This is certainly true for native assets on Ethereum, where high transaction fees and slow throughput make it difficult for newcomers to get involved in decentralized finance (DeFi).

Are layer 2 – centralized bridges sufficient?

It is a well-known misunderstanding in the crypto sphere that scaling of transactions in layer 1 blockchains can be achieved with layer 2 off-chain protocols. However, very little thought is given to what happens to the quality of these assets once they are bridged using an off-chain layer. This paper is a look at bridging protocols using Multiparty ECDSA that can be used to overcome the deficiencies of layer 2 off-chain bridges and fixed set validator bridges in existence today. To understand what those deficiencies are, we need to look deeper into what we are trying to bridge here.

If you need to understand the need for this assertion, it is important to know the context of this bridging mechanism. It is arguably agreed at this point that layer 1 transactions are not scalable because of the inherent need for security and immutability. It is also known that scalability, security, and programmability are mutually opposing properties in a blockchain, which has already been addressed in one of the articles we published prior to the launch of Polkadex. If you try to improve one of the areas, one of the others is compromised. When you are trying to bridge a blockchain asset, a perfect bridge is one that transfers all the properties of the source asset to the destination asset.

The core properties of open public blockchain are, what we call RIPCORD, an acronym used by Andreas Antonopoulos to measure viability of a blockchain:

- Revolutionary

- Immutable

- Public and auditable

- Collaborative with Governance

- Open and Permissionless

- Censorship Resistant

- Decentralized

We believe that any bridge protocol created should satisfy the above requirements to be truly effective in transferring the value from one public blockchain to the other. If the bridge is not capable of transferring almost all these properties, we will have to assume that the quality of asset on the layer 2 chain is different from its original. Then we call it an inefficient bridge, an accepted trade off to accomplish a larger use case. Though we need to assume that some compromise probably needs to be made in order to achieve user friendliness, it must not be at the expense of RIPCORD. It is the most important property that creates value for crypto assets issued in an open public blockchain.

Types of bridges available

Bridges are either custodial (also known as centralized or trusted) or noncustodial (decentralized or trustless). The difference explains who controls the tokens that are used to create the bridged assets. All wrapped bitcoin (WBTC) is held in custody by BitGo, making it a centralized bridge. Conversely, bridged assets on Wormhole are held by the protocol, meaning it is more decentralized.

For example, the a popular PoS bridge mentions the bridge as a “Proof-of-Stake system, secured by a robust set of external validators.” A robust fixed set without an open permissionless protocol is essentially centralized. When using a popular validator-driven bridge to transfer assets from the Ethereum network to their layer 2 network, costs of anywhere between $400 and $600 are not unheard of. It is also very slow, again, due to the validation process.

While hardline advocates of decentralization might venture that the custodial nature of WBTC makes it less secure than decentralized alternatives, bridges that decentralize custody over bridged assets aren't necessarily safer, as shown by the Wormhole bridge exploit. The token bridge between Ethereum and Solana saw 120,000 wETH tokens removed from the platform and distributed between the hacker’s Solana and ETH wallets.

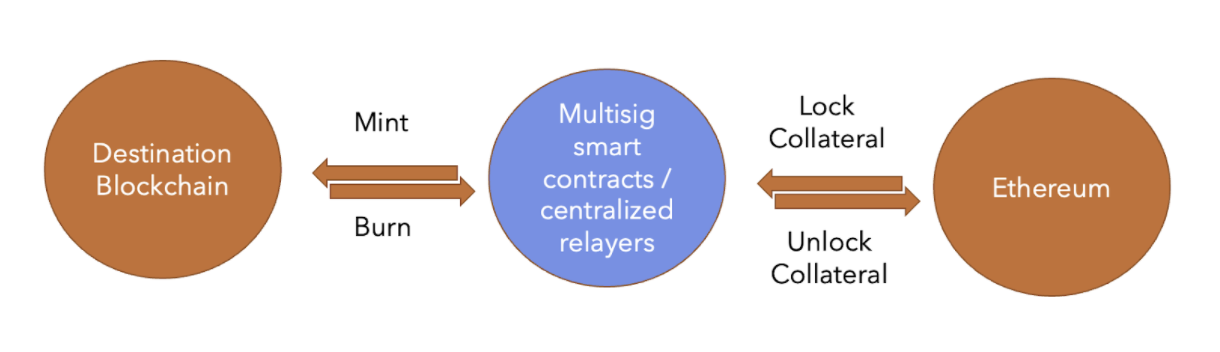

If you notice the above bridges, it is apparent that they are smart contract-based bridges held together by a limited number of onchain multisig wallets for which costs are high and performance is slow. The use of smart contracts and complex logic opens attack vectors among participants.

So, currently the existing systems looks similar to this:

The Quest for an elegant bridge solution

The quest for finding an elegant bridge solution, brought us to the following two technologies:

- Multiparty ECDSA.

- Light clients

Multiparty ECDSA is a library maintained by zengo.com, for the implementation of its multi-sig wallet services. This project is a Rust implementation of {t,n}-threshold ECDSA (elliptic curve digital signature algorithm).

Threshold ECDSA includes these protocols:

- Key Generation for creating secret shares.

- Signing for using the secret shares to generate a signature.

- Verification and validation of signatures using the knowledge of public keys.

ECDSA is used extensively for crypto-currencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum (secp256k1 curve), NEO (NIST P-256 curve) and much more. This library can be used to create MultiSig and ThresholdSig crypto wallet. For a full background on threshold signatures please read our Binance academy article Threshold Signatures Explained.

Multi-party computation (MPC) is a branch of cryptography that started with the seminal work of Andrew C. Yao, almost 40 years ago. In MPC, a set of parties that do not trust each other try to jointly compute a function over their inputs while keeping those inputs private.

As an example, let us say that n employees of a company want to know who is getting paid the most revealing to each other their actual salary. Here the private inputs are salaries and the output will be the name of the employee with the highest salary. Doing this computation using MPC we get that not even a single salary is leaked during the computation.

Threshold signature scheme (TSS) is the name we give to this composition of distributed key generation (DKG) and distributed signing of a threshold signature scheme.

Combining TSS with blockchains

Now, using TSS, we would have a set of n parties jointly computing the public key, each holding a secret share of the private key (the individual shares are not revealed to the other parties). From the public key, we can derive the address in the same way as in the traditional system, making the blockchain agnostic to how the address is generated. The advantage is that the private key is not a single point of failure anymore because each party holds just one part of it.

The same can be done when signing transactions. In this case, instead of a single party signing with their private key, we run a distributed signature generation between multiple parties. So, each party can produce a valid signature as long as enough of them are acting honestly. Again, we moved from local computation (single point of failure) to an interactive one.

It is important to mention that the distributed key generation can be done in a way that allows different types of access structures: the general “t out of n” setting will be able to withstand up to t arbitrary failures in private key related operations, without compromising security.

TSS vs Multisig

Both multisig and TSS are essentially trying to achieve similar goals, but TSS is using cryptography off-chain, while multisig happens on-chain. However, the blockchain needs a way to encode multisig, which might harm privacy because the access structure (number of signers) is exposed on the blockchain. The cost of a multisig transaction is higher because the information on the different signers also needs to be communicated on the blockchain.

TSS vs smart contracts

Over the years, researchers have found many uses for digital signatures, and some are surprisingly non-trivial. As mentioned, TSS is a cryptographic primitive that can greatly increase security. In the context of blockchains, we may say that many functionalities can be replaced with TSS-based cryptography. Decentralized applications, layer 2 scaling solutions, atomic swaps, mixing, inheritance, and much more can be built on top of a TSS framework. This would eventually allow for expensive and risky on-chain smart contract operations to be replaced by cheaper and more reliable alternatives.

Eureka Moment: THEA implementation

Based on these studies, we realized that even the TSS implementation on a much larger network is superior and inexpensive compared to on-chain multisig implementation even with a small number of public keys. THEA (Threshold ECDSA) protocol was hence developed to meet the bridging needs for Polkadex.

The challenge now was to adapt it to a larger network because all the implementation of TSS in a product environment so far was in much smaller private networks. We are still not sure how the system will behave in a large network of independent and potentially dishonest validators. The risk of manipulation and sabotage in the system is high when you have a large unknown validator set. There is currently no production level implementation of TSS on a large public network size of more than 10 or more validators with periodic key rotation. Thus designing the system and adapting it for our use case was really challenging.

We began by testing the signing protocol in a 3 node network, and gradually raised its size to 100. The biggest test case was to see if it was scalable. It worked with the 100 node test network, but the data transfer rates increased significantly because the participant nodes had to talk to each other and verify the data. In this time of sufficient bandwidth, such data transfer is justified to carry out this process. Validators will do all the cryptographic work and they will pass this info to the blockchain run time. Run time will then accept the key from validators, upon verifying that the signatures are correct, it will give back the required data to the validator. They can verify this because it is a deterministic data supplied by the blockchain runtime. The validators then aggregate the signatures and then any one such node or an incentivised third party can send the signature+data to the Ethereum smart contract that holds the user funds for either withdrawal or deposit. The node that submits this data will have to pay network fees. By submitting a reclaim process to the Polkadex treasury, validators can be reimbursed these fees plus an interest for helping to execute transactions. It is a separate program that handles the data processed by the smart contract, the THEA signature thus passed has admin control to the smart contract that will execute the transaction. We also optimized the runtime and costs by batching the transactions to achieve maximum efficiency in cost and time. Key rotation of these validators happens every 24 hours.

THEA wallet: As opposed to hierarchical deterministic wallets, threshold wallets used in THEA are more complex. Although it is possible to generate an HD structure, its generation must be computed in a distributed manner, as another MPC protocol. The parties need to jointly decide on what is the next key to be used. In other words, each party will have a seed phrase of its own. The seed phrases are generated separately and never combined so that one party alone can’t derive the private keys from its seed.

Lightclients

Now that threshold signatures are available to decentralize the ownership of funds moving in and out, our next challenge was verifying transactions from the layer 1 blockchain we are attempting to bridge. We decided to make use of light clients because we cannot expect the validators to run full nodes of layer 1 chains which are extremely heavy and expensive for the reward mechanism to be profitable. Light clients are crucial elements in blockchain ecosystems. They help users access and interact with a blockchain in a secure and decentralized manner without having to sync the full blockchain. A light client or light node is a piece of software that connects to full nodes to interact with the blockchain. Unlike their full node counterparts, light nodes don’t need to run 24/7 or read and write a lot of information on the blockchain. In fact, light clients do not interact directly with the blockchain; they instead use full nodes as intermediaries. Light clients rely on full nodes for many operations, from requesting the latest headers to asking for the balance of an account.

As a starting point, a light client needs to download the block headers of the blockchain. The light client does not need to trust the full node for every request that it makes to the full node. This is because the block headers contain a piece of information called the Merkle tree root. The Merkle tree root is like a fingerprint of all information on the blockchain about account balances and smart contract storage. If any tiny bit of information changes, this fingerprint will change as well. Assuming that the majority of the miners are honest, block headers and therefore the fingerprints they contain are assumed to be valid. A light client may need to request information from full nodes such as the balance of a specific account. Knowing the fingerprints for each block, a light client can verify whether the answer given by the full node matches with the fingerprint it has. This is a powerful tool to prove the authenticity of information without knowing it beforehand. So, we incorporated the light clients onto the validator code.

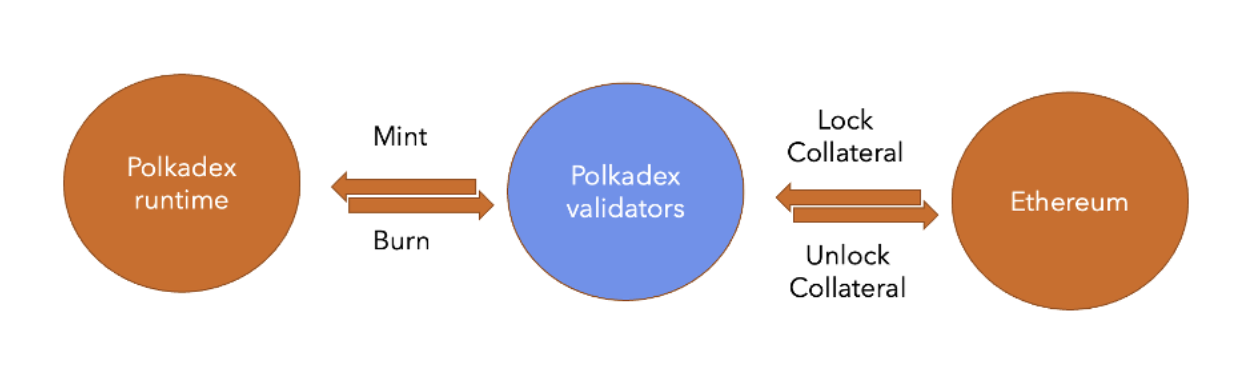

THEA == TSS + Lightclients in RUST

Currently, our validator set is around 150. On a high level, the bridge looks like this:

Polkadex validators act as relayers which are as decentralized as the Polkadex blockchain. THEA uses multi-party ECDSA, hence there is no central point of attack. Effectively, THEA allows Polkadex Blockchain validators to hold wallets in other layer 1 blockchains.

- Thea uses Multi-party ECDSA to handle signature and key rotation policy

- All Thea validators rotate their private key share every 24 hours.

- Cryptography used in Thea is elliptic curve, 𝑦^2=𝑥^3+ax+b

- First integration of Thea is with Ethereum, hence bridging all ERC20 tokens.

- Confirmation for bridging assets to THEA is the same as the parent chain confirmation times.

- THEA uses light clients for verifying transactions on the parent chain.

- THEA accepts the participatory set if (2 * n + 1) / 3 join as THEA validators, where n=total number of validators.

- THEA accepts the signature if signed by (2 * n + 1) / 3 of the participatory set.

- All deposit fees for confirmation on the Polkadex blockchain are funded by the treasury hence all deposits are free for all users.

- All withdrawals carry the same fees as the destination layer 1 chain + a fee to be paid to the validators.

Conclusion: We have proposed a system of bridging public blockchain assets without relying on trust and transferring its entire RIPCORD properties. We started by exploring different bridges that utilize smart contracts and collateral-based assets. This is incomplete because it forces the bridged assets to rely on a limited number of participants or a centralized relayer set. The proposed solutions are relying on on-chain multisig wallets which are expensive and slow. To solve this, we propose the bridged assets to be held by a decentralized set of validators who use TSS and key rotation. The inherent randomness of decentralized and incentivized PoS validator selection makes an attack to gain access to the smart contract extremely expensive to collude within the given time frame.

Examples of open, public blockchain quoted in the above paper are: Ethereum, Bitcoin etc.

References

- https://101blockchains.com/public-blockchain/

- https://stonecoldpat.medium.com/a-note-on-bridges-layer-2-protocols-b01f8fc22324

- https://docs.polygon.technology/docs/develop/ethereum-polygon/getting-started

- https://umbrianetwork.medium.com/bridging-eth-from-ethereum-to-polygon-how-do-blockchain-bridges-vary-42d342a249dd

- https://www.coindesk.com/learn/what-are-blockchain-bridges-and-how-do-they-work/

- https://cointelegraph.com/news/wormhole-token-bridge-loses-321m-in-largest-hack-so-far-in-2022

- https://github.com/ZenGo-X/multi-party-ecdsa

- https://academy.binance.com/en/articles/threshold-signatures-explained

- https://www.parity.io/blog/what-is-a-light-client/